Dr. Gideon Fell

"It isn't every day, you know," the doctor explained, apologetically, "that a man gets the opportunity to write the story of his own murder."

--Dr. Gideon Fell in Hag's Nook, chapter 11

After writing four novels about the satanic and cruel detective Henri Bencolin, John Dickson Carr wanted to create a softer, more likeable, detective. He did so with Dr. Gideon Fell.

If Bencolin was "Mephistopholes smoking a cigar," Dr. Fell was Old King Cole (cf. The Mad Hatter Mystery).

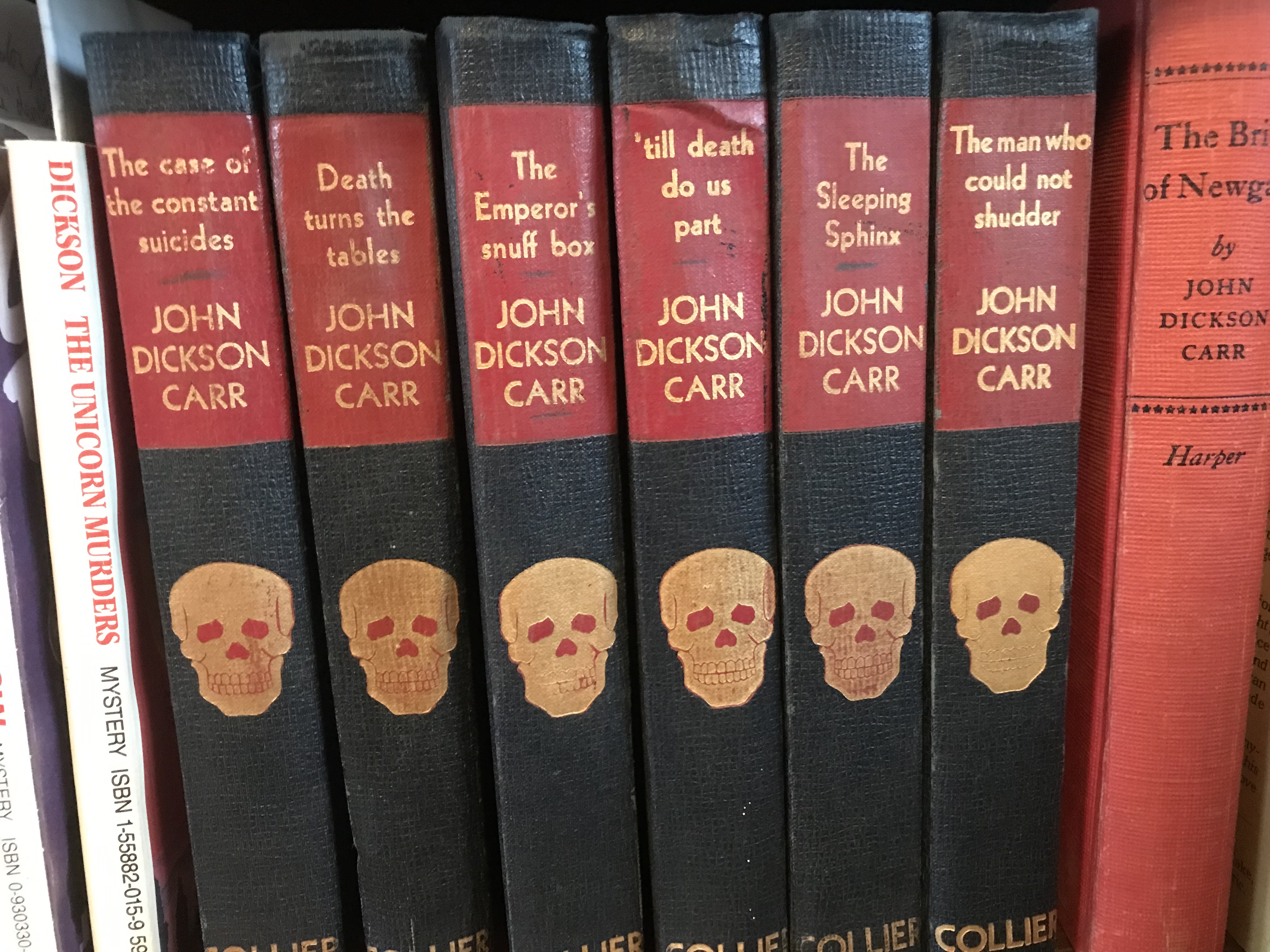

Some John Dickson Carr Books (Above)

Physically, Fell was modeled after G. K. Chesterton. But Carr, who was reading history about the Restoration in his spare time, may have taken the detective's name from Dr. John Fell, Bishop of Oxford. Douglas Greene finds it more likely that he discovered the similarity of names after he created Fell.

The historical Dr. John Fell was known as a disciplinarian, and there is an interesting story about him: It seems a student named Tom Brown got into some trouble, and Dr. Fell challenged him to translate a quatrain from a Latin poet. If Brown was able to do so successfully, Fell would let him off; if not, he would be dismissed from the college. According to the story, Brown translated the passage as:

| I do not love thee, Dr. Fell.

The reason why I cannot tell. But this I know and know full well, I do not love thee, Dr. Fell. |

The story is that Fell admired Brown's response and allowed him to stay.

Another version of the story substitutes "I do not like thee, Dr. Fell" for "I do not love thee, Dr. Fell" (emphasis mine). It's difficult to resolve which is the original version (although the Dr. Fell books I've read quote the "love" version). Even Greene quotes one version in John Dickson Carr: The Man Who Explained Miracles (1995) and the other version in his 1985 introduction to the International Polygonics, Ltd. reprint of Hag's Nook. In this introduction, Greene writes:

| Fell himself sometimes quotes this verse, and so do the murderers he tracks down, but otherwise he does not take after his rather stern namesake. His appearance and personality were based on Carr's literary idol, G. K. Chesterton, the essayist and author of the Father Brown detective stories. The formality of Fell's speech was borrowed from Dr. Samuel Johnson, a fact which probably explains why Fell is described in Hag's Nook as a lexicographer. |

Click Image to

Order from Amazon

(As an Amazon Associate

I earn from

qualifying purchases.)

Click the image below to

Read the Reviews:

Introducing Dr. Gideon Fell

In the first Dr. Gideon Fell mystery, Hag's Nook (© 1933 by John Dickson Carr), Dr. Fell is introduced in the following passage from chapter one:

| The old lexicographer's study ran the length of his small house. It was a raftered room, sunk a few feet below the level of the door; the latticed windows at the rear were shaded by a yew tree, through which the late afternoon sun was striking now....

Tad Rampole glanced across at his host. Filling a deep leather chair with his bulk, Dr. Gideon Fell was tapping tobacco into a pipe and seemed to be musing genially over something the pipe had just told him. Dr. Fell was not too old, but he was indubitably a part of this room. A room--his guest thought--like an illustration out of Dickens. Under the oak rafters, with smoke-blackened plaster between, it was large and dusky; there were diamond-paned windows above great oak mausoleums of bookshelves, and in this room, you felt, all the books were friendly. There was a smell of dusty leather and old paper, as though all those stately old-time books had hung up their tall hats and prepared to stay. Dr. Fell wheezed a little, even with the exertion of filling his pipe. He was very stout, and walked, as a rule, with two canes. Against the light from the front windows his big mop of dark hair, streaked with a white plume, waved like a war-banner. Immense and aggressive, it went blowing before him through life. His face was large and round and ruddy, and had a twitching smile somewhere above several chins. But what you noticed there was the twinkle in his eye. He wore eyeglasses on a broad black ribbon, and the small eyes twinkled over them as he bent his big head forward; he could be fiercely combative or slyly chuckling, and somehow he contrived to be both at the same time. "You've got to pay Fell a visit," Professor Melson had told Rampole. "First, because he's my oldest friend, and, second, because he's one of the great institutions of England. The man has more obscure, useless, and fascinating information than any person I ever met. He'll ply you with food and whisky until your head reels; he'll talk interminably, on any subject whatever, but particularly on the glories and sports of old-time England. He likes band music, melodrama, beer, and slapstick comedies; he's a great old boy, and you'll like him." There was no denying this. There was a heartiness, a naivete, an absolute absence of affection about his host which made Rampole at home five minutes after he had met him. |

Anthony Boucher wrote, "Hag's Nook is Dr. Fell's first recorded case, and thirty years later (1962) it still seems to rank among his best."

Dr. Fell Lectures

Dr. Fell likes to lecture and often does so spontaneously, to the chagrin of some of his colleagues. In Hag's Nook (chapter 14), for example, Carr writes:

| "But look at the blasted thing!"

exploded Sir Benjamin, picking up Rampole's copy from the hearth and slapping it.

"Look here, in the last verse. It doesn't make sense. 'The Corsican was vanquished

here, Great mother of all sin.' If that means what I think it does, it's a bit

rough on Napoleon."

Dr. Fell took the pipe out of his mouth. "I wish you'd shut up," he said, plaintively. "I feel like lecturing, I do. I was going on from Trithemius to Francis Bacon, and then--" "I don't want to hear any lecture," interposed the chief constable. "I wish you'd have a look at the thing. I don't ask you to solve it. But stop lecturing and just look at it." Sighing, Dr. Fell came to the centre table, where he lighted another lamp and spread the paper out before him. The pipe smoke slowed down to thin, steady puffs between clenched teeth. |

|

Click Image to Click the image below to |

Click Image to Click the image below to |

The Locked Room Lecture

In The Three Coffins (a.k.a., The Hollow Man), Dr. Fell interrupts the narrative of the novel to lecture to Inspector David Hadley, Ted Rampole (we knew him as "Tad" Rampole in Hag's Nook), and "fussy baldheaded little" Pettis. This Locked Room Lecture (chapter 17) is one of the most famous chapters written in detective, crime, and murder mystery fiction, and has been anthologized widely. In it, Carr (or, rather, Gideon Fell) discusses the techniques and tricks that writers of detective stories often employ. Dr. Fell begins by lecturing:

| Dr. Fell looked more than ever like

a feudal baron. He glanced with contempt at the demi-tasse, which he seemed in

danger of swallowing cup and all. He made an expansive, settling gesture with his

cigar. He cleared his throat.

"I will now lecture," announced the doctor, with amiable firmness, "on the general mechanics and development of that situation which is known in detective fiction as the 'hermetically sealed chamber.'" Hadley groaned. "Some other time," he suggested. "We don't want to hear any lecture after this excellent lunch, and especially when there's work to be done. Now, as I was saying a moment ago--" "I will now lecture," said Dr. Fell, inexorably, "on the general mechanics and development of the situation which is known in detective fiction as the 'hermetically sealed chamber.' Harrumph. All those opposing can skip this chapter. Harrumph. To begin with, gentlemen! Having been improving my mind with sensational fiction for the last forty years, I can say--" "But, if you're going to analyze impossible situations," interrupted Pettis, "why discuss detective fiction?" "Because," said the doctor, frankly, "we're in a detective story, and we don't fool the reader by pretending we're not. Let's not invent elaborate excuses to drag in a discussion of detective stories. Let's candidly glory in the noblest pursuits possible to characters in a book." |

The Three Coffins -- The Best Locked-Room Mystery Ever Written?

|

The Three Coffins is considered by many people to be the best (or, at least one of the best) locked-room mysteries ever written. S. T. Joshi (John Dickson Carr: A Critical Study, Copyright ©1990 by Bowling Green State University Popular Press), writes, "This [The Three Coffins] is one of several--perhaps many--Carr novels that one ought to read twice in succession: the first to be bamboozled, the second to see how it was done." |

Click Image to Click the image below to |

Note: The Judas Window, The Peacock Feather Murders, and He Wouldn't Kill Patience feature Carr's detective Sir Henry Merrivale. |

Greene writes: "About ten years ago [Greene's biography of Carr was published in 1995], a group of mystery experts was polled to determine the greatest locked-room novels ever written. The Three Coffins came in first, with almost twice as many points as the second-place novel" (Douglas Greene, John Dickson Carr: The Man Who Explained Miracles, New York: Otto Penzler Books, 1995, p. 152). In an end note, Greene cites "Edward D. Hoch, ed., All But Impossible! An Anthology of Locked Room and Impossible Crime Stories (New Haven: Ticknor & Fields, 1981), pp. ix-xi. Four additional Carr novels appeared in the top fifteen: The Crooked Hinge, The Judas Window, The Peacock Feather Murders, and He Wouldn't Kill Patience" (Greene, chapter 6, endnote 28). |

The IPL [International Polyglonics, Ltd.]: New York City] version includes the following blurb: "And just a few years ago, a survey of seventeen mystery mavens rated The Three Coffins as the best all-time locked room novel by a margin of 2 to 1!"

John Pugmire gives a more complete account of the poll and includes the results here.

John Dickson Carr --

Master of Supernatural Overtones,

the Locked Room Mystery,

and the "Impossible Crime"

The major elements which characterize John Dickson Carr's detective fiction include great description of scenery (often tinged with supernatural overtones), the locked room motif, and the "impossible crime." (The Three Coffins, and other books by John Dickson Carr, include all three.)

- A Supernatural Theme. Dorothy L. Sayers wrote that the most satisfying type of detective story often had supernatural overtones but a rational, logical explanation. (See her introduction to The Omnibus of Crime.) Carr soon proved himself a master of this form, although on at least one occasion he ended his book by implying a supernatural explanation.

- The Locked Room Mystery. Carr's use of this theme was unparalleled in the history of detective, crime, and murder mystery books. Reviewers and critics have said that the locked room theme is usually better relegated to the short story form because it is difficult to sustain in novel-length fiction. (Many who attempted to do so were unsuccessful.) Yet Carr successfully employed it time and again.

- The "Impossible Crime." A murder victim is discovered in wet sand, snow, or mud with only his own footprints evident. Or a guest at a swimming party dives into a pool in the midst of many people and disappears in full view of witnesses. Like the locked room mystery, the impossible crime is difficult to sustain in novel-length fiction. It is apparently even harder to combine the locked room theme with the impossible crime in the same book. While other writers attempted these feats unsuccessfully, John Dickson Carr pulled them off repeatedly.

|

Click Image to Click the image below to |

Click Image to Click the image below to |

|

Click Image to Click the image below to |

Click Image to Click the image below to |

Dr. Fell Books

- Hag's Nook (1933)

- The Mad Hatter Mystery (1933)

- The Eight of Swords (1934)

- The Blind Barber (1934)

- Death-Watch (1935)

- The Three Coffins (1935) (The Hollow Man)

- The Arabian Nights Murder (1936)

- To Wake the Dead (1938)

- The Crooked Hinge (1938)

- The Problem of the Green Capsule (1939) (The Black Spectacles)

- The Problem of the Wire Cage (1939)

- The Man Who Could Not Shudder (1940)

- The Case of the Constant Suicides (1941)

- Death Turns the Tables (1942) (The Seat of the Scornful)

- Till Death Do Us Part (1944)

- He Who Whispers (1946)

- The Sleeping Sphinx (1947)

- Below Suspicion (1949)

- The Dead Man's Knock (1958)

- In Spite of Thunder (1960)

- The House at Satan's Elbow (1965)

- Panic in Box C (1966)

- Dark of the Moon (1967)

- Fell and Foul Play (1991) -- Compiled by Douglas Greene

|

Click Image to Click the image below to |

Click Image to Click the image below to |

|

Click Image to Click the image below to |

Click Image to Click the image below to |

Amazon and the Amazon logo are trademarks of Amazon.com, Inc. or its affiliates.

(This is a link through which I make a small commission if you buy. See here for more details.)